Name One Justification Southern Slaveholders Have for the Continuation of Slavery

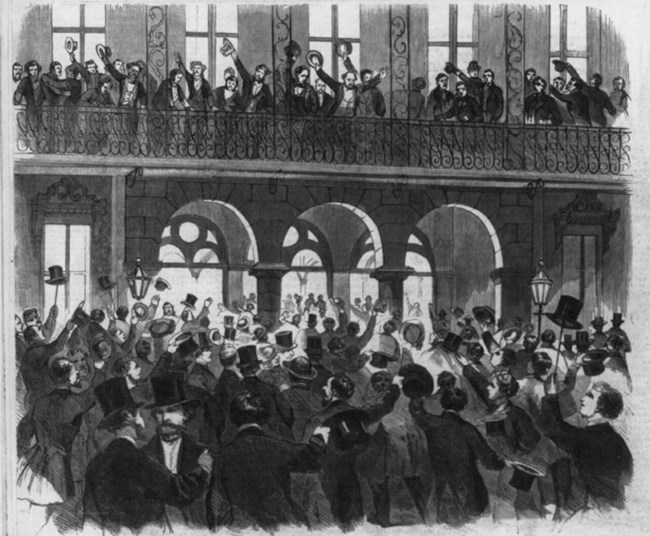

Library of Congress

The role of slavery in bringing on the Civil War has been hotly debated for decades. One important way of approaching the issue is to look at what contemporary observers had to say. In March 1861, Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, gave his view:

The new [Confederate] constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution — African slavery as it exists amongst us — the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution . . . The prevailing ideas entertained by . . . most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. . . Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of . . . the equality of races. This was an error . . .

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner–stone rests upon the great truth, that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery — subordination to the superior race — is his natural and normal condition.

— Alexander H. Stephens, March 21, 1861, reported in the Savannah Republican, emphasis in the original

New York Public Library Digital Collections

Today, most professional historians agree with Stephens that slavery and the status of African Americans were at the heart o the crisis that plunged the U.S. into a civil war from 1861 to 1865. That is not to say that the average Confederate soldier fought to preserve slavery or that the North went to war to end slavery. Soldiers fight for many reasons — notably to stay alive and support their comrades in arms — and the North's goal in the beginning was preservation of the Union, not emancipation. For the 200,000 African Americans who ultimately served the U.S. in the war, emancipation was the primary aim.

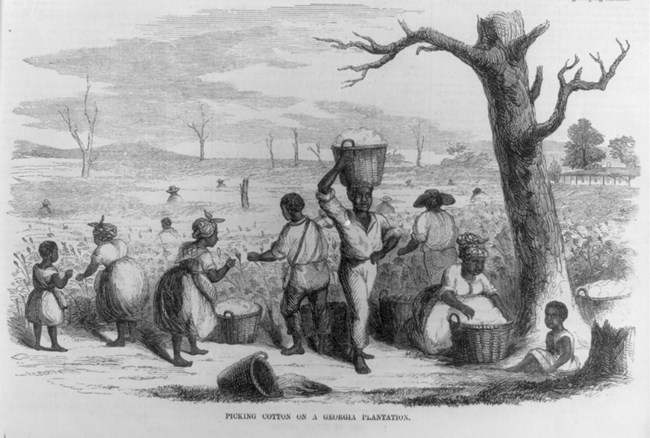

The roots of the crisis over slavery that gripped the nation in 1860–1861 go back to the nation's founding. European settlers brought a system of slavery with them to the western hemisphere in the 1500s. Unable to find cheap labor from other sources, white settlers increasingly turned to slaves imported from Africa. By the early 1700s in British North America, slavery meant African slavery. Southern plantations using slave labor produced the great export crops — tobacco, rice, forest products, and indigo — that made the American colonies profitable. Many Northern merchants made their fortunes either in the slave trade or by exporting the products of slave labor. African slavery was central to the development of British North America.

Although slavery existed in all 13 colonies at the start of the American Revolution in 1775, a number of Americans (especially those of African descent) sensed the contradiction between the Declaration of Independence's ringing claim of human equality and the existence of slavery. Reacting to that contradiction, the Northern states decided to phase out slavery following the Revolution. The future of slavery in the South was debated, and some held out the hope that it would eventually disappear there as well.

Library of Congress

When the U.S. Constitution was written in 1787, however, the interests of slaveholders and those who profited from slavery could not be ignored. Although slaves could not vote, white Southerners argued that slave labor contributed greatly to the nation's wealth. The Constitution therefore gave representation in the Congress and the electoral college for 3/5ths of every slave (the 3/5ths clause). The clause gave the South a role in the national government far greater than representation based on its free population alone would have given it. The Constitution also provided for a fugitive slave law and made 1807 the earliest year that Congress could act to end the importation of slaves from Africa.

The Constitution left many questions about slavery unanswered, in particular, the question of slavery's status in any new territory acquired by the U.S. The failure to deal forthrightly and comprehensively with slavery in the Constitution guaranteed future conflict over the issue. All realistic hope that slavery might eventually die out in the South ended when world demand for cotton exploded in the early 1800s. By 1840, cotton produced in the American South earned more money than all other U.S. exports combined. White Southerners came to believe that cotton could be grown on with slave labor. Over time, many took for granted that their prosperity, even their way of life, was inseparable from Africa slavery.

Library of Congress

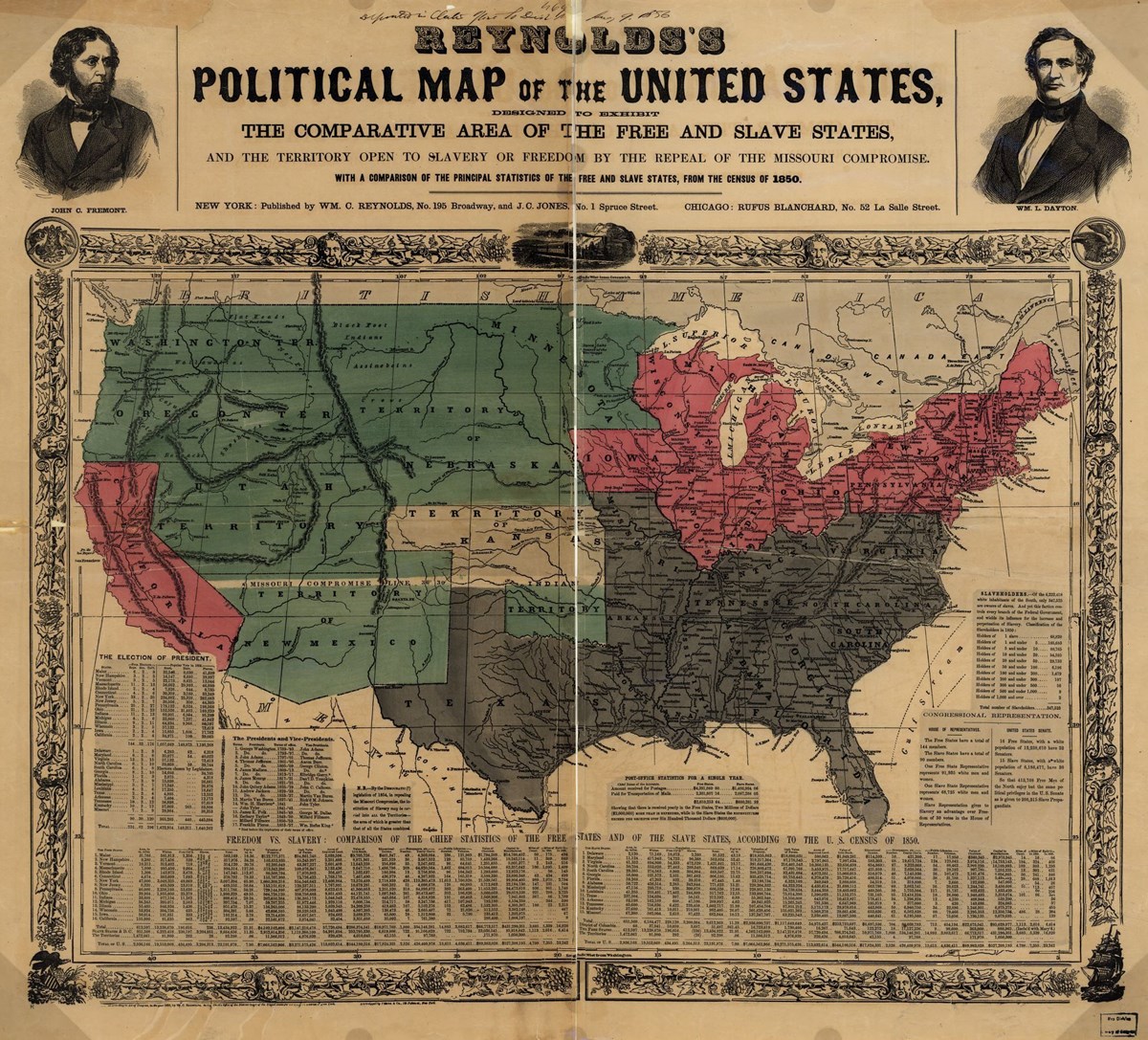

In the decades preceding 1860, Northerners increasingly supported the right of farmers and workers to enjoy the fruits of their labor and try to better themselves. Slavery did not fit with this view. Many Northerners opposed its presence in the territories, which were viewed as the birthright of ambitious, free white men. The proposed admission of Missouri as a slave state in 1820 provoked a national debate over slavery. After much discussion, the 1820 Missouri Compromise was worked out. Under its terms, Maine was admitted as a free state at the same time that Missouri came in as a slave state, maintaining the balance between slave and free states. Additionally, Congress prohibited slavery in all western territories lying above latitude 36° 3o' (the southern boundary of Missouri).

The Missouri Compromise quieted agitation over slavery for only a while. In the 1830s, concerns over the issue resurfaced for several reasons. One was the appearance in the North of a tiny number of very persistent agitators calling for the immediate abolition of slavery (the abolitionists). Another was the bloody 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion in Virginia. White Southerners believed Northern abolitionists encouraged slave revolts, while Southern efforts to silence the abolitionists aroused Northern fears about freedom of speech.

Later, U.S. victory in the Mexican War of 1846–1848 brought the nation vast new acreage in the West. Once again, the status of slavery in the territories became a hot issue. A new agreement, the Compromise of 1850, was required when the California Territory sought to join the Union. Aspects of the compromise included 1) admission of California as a free stat 2) a stronger fugitive slave law; 3) assurance that Congress would not interfere with the interstate traffic in slaves in the South; and 4) prohibition of the slave trade in the District o Columbia. The compromise left open the status of slavery in the other areas won from Mexico. Then, in 1854, the Kansas– Nebraska Act effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, causing more violent disputes over slavery. Pro– and anti– slavery factions turned the Kansas Territory into a bloody battleground.

Library of Congress

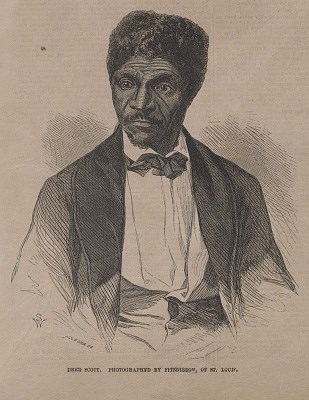

Mostly as a result of tensions over slavery, a new party, the Republicans, arose in the North in the 1850s. The Republicans made prohibition of slavery in the territories their chief issue. The party was the first in the nation's history to draw its support from one section only. Inevitably, the party aroused deep anger in the South. Attitudes in the two sections of the nation continued to harden in the late 1850s. In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court in the Dred Scott decision ruled that Americans of African descent were not U.S. citizens. A failed effort to start a slave uprising in Virginia by abolitionist John Brown in 1859 spread fear and distress across the South.

The presidential election of 1860 was fought entirely along sectional lines. The Democratic Party finally splintered over slavery, with the party fielding two candidates. The Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. His platform included government support of road and harbor projects and higher tariffs (import taxes) to protect American industry, in addition to keeping slavery out of the territories. Lincoln won the election by sweeping the Northern states, while failing to gain a single electoral vote in the Deep South. Spurred by South Carolina, the states of the Deep South decided that limitation of slavery in the territories was the first step toward a total abolition of slavery.

Library of Congress

One by one, seven states — South Caroline, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas – left the Union. Lincoln hoped desperately to maintain the Union without war. When he decided to resupply the U.S. army at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, Confederate forces fired on the fort. Lincoln then asked for 75,000 volunteers to put down the rebellion. This prompted Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas to join the Confederacy. Civil war had come.

There were many sectional differences in 19th–century America. Differences over slavery were the only ones that could not be settled by peaceful means. Much evidence from that time shows that the secession of seven Deep South states was caused mostly by concerns over the future of slavery. When Mississippi seceded, she published a "Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Include and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union." It stated:

"Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery... Utter subjugation awaits us in the Union, if we should consent longer to remain It is not a matter of choice, but of necessity. We must either submit to degradation, and to the loss of property worth four billions of money [the estimated total market value of slaves], or we must secede from the Union framed by our fathers, to secure this as well as every other species of property."

Slavery, Lincoln, and the Civil War

Source: https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/slavery-cause-civil-war.htm

0 Response to "Name One Justification Southern Slaveholders Have for the Continuation of Slavery"

Post a Comment